PSD3 and PSR: an architectural reset for European digital payments

Four hundred billion dollars in payment fraud losses over the coming decade: that is the forecast that pushed EU regulators into a ground up reform of the rules. The PSD3 and PSR package introduces uniform standards across all of Europe and shifts the burden of responsibility from the customer to financial institutions. Banks now have eighteen months to rebuild their authentication systems and put in place mechanisms that automatically block fraud attempts before the money leaves the account.

Table of contents

Key takeaways

- No more flexibility: the new regulation imposes identical rules across the entire Union. The time for legal workarounds is over, and penalties for breaking the rules can reach 4% of a company’s turnover.

- Technology under pressure: banks must create transparent dashboards where customers can check their consents. The safety net for fallback systems disappears, so interfaces built for third parties must work as reliably as the bank’s own app.

- Authentication changes: identity verification can no longer depend solely on a smartphone. Banks must offer alternative methods, such as hardware security keys or computer based biometrics.

- New fraud rules: the bank must return the full amount to the customer if a thief impersonated a member of staff. This forces banks to detect psychological manipulation attempts before the theft happens.

- Delegated verification: merchants can verify the customer’s identity themselves, using tools like Apple Pay. This makes shopping easier, but in return the merchant takes on full liability for any fraud.

- Equal access to systems: independent financial firms gain direct entry to settlement systems. They no longer need to ask banks to act as middlemen for processing transfers.

- Unified security: payment protection stops being a standalone project. It becomes an integral part of the institution’s overall technological resilience.

The end of fragmentation: why the PSR is the biggest payments shakeup in a decade

The European Commission described PSD3 as “evolution, not revolution,” but the change to how the rules are built tells a different story. The single biggest shift is the split between a Directive (PSD3, still needing separate transposition in every member state) and a directly applicable Regulation (PSR). As analyses by both Deloitte Luxembourg and Deloitte UK show, this split removes the problem that paralysed the market for years: divergent national interpretations that made PSD2 implementation across 27 member states so painful.

PSR also pulls the Regulatory Technical Standards on strong customer authentication (SCA) and secure communication straight into the body of the regulation, rather than delegating them to separate EBA standards. Experts at EY Belgium and EY Netherlands note that the middle layer that previously left room for creative interpretation and for delays disappears.

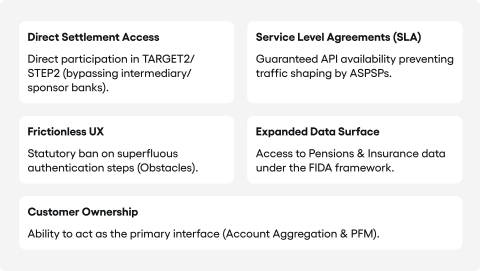

There is another structural change with far reaching consequences: the package merges the Electronic Money Directive (EMD2) into PSD3. E money institutions become a subcategory of payment institutions under a single licensing regime, as EY Belgium explains. Nonbank payment institutions and e money institutions gain the right to access EU payment systems directly, including TARGET2, a privilege reserved until now for banks alone. Data cited by Deloitte Luxembourg and PwC Netherlands confirm this shift.

Deloitte Luxembourg called this the creation of a genuinely “level playing field” between banks and nonbank players. PwC Netherlands flagged an easy to miss detail: the agreement requires existing nonbank payment service providers (PSPs) to reobtain their licences within 30 months. Waiting around is not an option. Firms must act to keep their right to operate.

The legislative calendar leaves no room for doubt about the pace of change. The Commission published its proposals in June 2023; Parliament adopted amendments in April 2024; the Council agreed its position in June 2025; the trilogue deal landed in November 2025. These milestones are documented by EY Belgium. Formal adoption is expected around mid 2026, starting an 18 month transition period. Full compliance means late 2027 or early 2028, according to Deloitte UK’s Regulatory Outlook 2026.

That same Deloitte UK report carried a warning worth taking seriously: experience with PSD2 suggests the PSD3 package will divert resources away from new payment product development towards compliance work. For institutions that had planned aggressive digital expansion in the coming years, this means balancing product ambitions against a growing regulatory burden.

Fines for noncompliance have risen to 4% of annual turnover or EUR 20 million, directly modelled on the GDPR approach, EY Belgium highlight. For a large European bank turning over tens of billions of euros, a 4% fine is the kind of number that boards and supervisory councils pay attention to.

Mobile architecture under pressure: designing UX when compliance shapes the interface

PSD3/PSR touches the API layer, consent management, data access and third party cooperation. The real difficulty, though, is not the technical implementation itself; it is designing a user experience that meets regulatory requirements without driving customers away. This tension between compliance and usability will define the quality of digital banking for years to come.

Dedicated APIs with no fallback exit

PSD2 allowed banks to give third party providers (TPPs) access through dedicated APIs or modified customer interfaces with a fallback mechanism. PSD3/PSR removes the fallback entirely, as EY Belgium describe. Around 6,000 account servicing payment service providers (ASPSPs) across the EU must now offer a dedicated interface for data sharing with account information service providers (AISPs) and payment initiation service providers (PISPs) that works as quickly and reliably as the bank’s own customer facing interface, a point underlined by both EY Belgium. Screen scraping is banned once and for all.

As the EBA openly acknowledged, the lack of a single API standard created real problems for TPPs operating across several countries. PSD3 does not impose one standard; the EBA judged that “the industry itself is best placed to design it”, but sets significantly higher minimum requirements and bans artificial obstacles, such as adding extra authentication steps to TPP pathways. Premium paid APIs covering things like dynamic recurring payments or payment guarantees remain permissible under commercial agreements. The distinction matters: regulation forces a quality baseline, but does not close the door to commercialising premium services.

The permission dashboard: a moment of truth for UX

Every PSP offering online accounts must build a permission dashboard letting users see in real time which TPPs access their data, and revoke or grant permissions, as detailed by EY Belgium and EY Netherlands. TPPs must feed permission data back to the PSP so dashboards stay in sync, creating a new obligation for real time data exchange.

On paper, this sounds like a simple regulatory box to tick. In reality, it is one of the hardest design challenges European digital banking has faced. For most bank customers, seeing a list of third party firms with access to their data will be an entirely new (and potentially alarming) experience.

A badly designed dashboard, a dry list of company names with access dates and “revoke” buttons, will trigger a defensive reaction: mass revocations, more calls to customer service, and a drop in trust towards the bank for suddenly “revealing” that someone had access.

A well designed dashboard should hit three targets at once.

First: clarity without panic. This means showing permissions in the context of the benefits they bring. A message like “App X helps you manage your budget by analysing your transactions” lands very differently from “Company X Ltd. has had access to your account since 14/03/2025.” Both statements are true, but the first builds understanding while the second builds anxiety.

Second: fine grained control with sensible defaults. Users should be able to revoke permissions with a single tap, but the interface should not suggest that revoking is the recommended action. This is a subtle but fundamental difference in choice architecture, and it will decide whether the dashboard becomes a trust building tool or a machine for destroying the open banking ecosystem.

Third: education built into the flow. Banks will need to explain to users why they are suddenly seeing a list of third party firms with access to their data. Short, contextual tooltips and an FAQ section baked into the dashboard itself (“What is an AISP?”, “Can these firms withdraw my money?”, “Why does my bank share my data?”) will turn out to be essential for a successful rollout.

Institutions that treat the permission dashboard as a tool for building customer relationships, rather than a checked box on a compliance list, will gain a measurable edge in retention. Forrester’s review of European mobile banking apps (Q3 2024) noted that transparency in data management has become one of the top differentiators of digital experience in financial services.

From monolith to microservices: architecture for FIDA

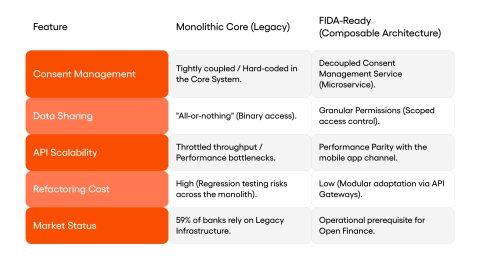

The FIDA (Financial Data Access) rules, running in parallel with PSD3/PSR, extend open banking into open finance, covering mortgages, savings, investments, pensions and insurance data. An analysis described the target model as a set of independent microservices delivered by multiple providers, combining offerings into useful solutions for shared customers. This is a vision unlike the monolithic systems that underpin most European banking today, different not in the details but in the very architectural assumptions.

For banks whose core banking systems operate as a single massive monolith, FIDA changes the game in ways cosmetic adjustments cannot fix. A survey published by Accenture, covering 326 executives across 18 markets (December 2024), found that 59% of banks still struggle with outdated payments IT. The problem is specific: a monolithic architecture where account logic, authentication, consent management and TPP data sharing all live in one codebase cannot flexibly meet FIDA requirements. The regulation assumes banks will share different data types with different authorised recipients, and monoliths simply cannot do that.

Moving to a microservices architecture, with separate services for consent management, API provisioning, transaction monitoring and authentication, follows directly from the regulation. When FIDA assumes a bank will share investment portfolio data with one entity and current account history with another, a monolith cannot adapt to such granular permissions without a major rebuild. This is not about good practice. It is a necessary condition for legal compliance.

BCG estimated that the EU financial sector could gain EUR 4.6 to 12.4 billion from expanded data access under FIDA, against one off implementation costs of EUR 2.2 to 2.4 billion. The cost benefit ratio is clearly positive, but only if institutions build architecture capable of supporting this ecosystem.

Changes to AISP and PISP access

Access rules for different categories of third party providers are changing significantly. For AISPs, strong authentication is required only at first access, after which a 180 day window opens; on subsequent accesses the AISP applies its own SCA. This simplification is described in EY Netherlands’ analysis of the PSR and should improve how smoothly financial data aggregation apps work.

Banks (ASPSPs) must give payment initiation service providers (PISPs) the account holder’s name, identifier and available currencies before an operation begins, as EY Belgium specifies. Verification of Payee will cover all bank transfers, requiring a real time name matching system across the entire SEPA ecosystem. Analysis confirms that before every transfer, the bank will need to check whether the account number actually belongs to the person or company named as the recipient, and warn the customer if there is a mismatch.

SCA after the revolution: from PINs and SMS codes to risk adaptive biometrics and FIDO2 keys

Strong Customer Authentication under PSD3/PSR is going through its most significant redesign since it was first introduced. The scale of change is visible even at a purely quantitative level: as EY Netherlands points out, the term “SCA” appears 70 times in the PSD3 text, compared with just 8 in PSD2. That disparity speaks for itself.

Factor flexibility: the end of artificial barriers

PSD2 required authentication factors from two different categories: knowledge, possession, inherence. PSD3/PSR relaxes this rule in a way that reflects technological reality: two independent factors from the same category are now acceptable, provided they are technically independent, meaning compromising one does not allow bypassing the other. Reports by EY Belgium and EY Netherlands confirm this change. A fingerprint and facial recognition, both from the “inherence” category, can together satisfy SCA requirements. This is a practical acknowledgement that today’s phones and laptops offer several biometric methods in a single device, and there is no reason for regulation to force users into artificial switching between categories.

The ban on smartphone dependency: FIDO2 keys, WebAuthn and next generation tokens

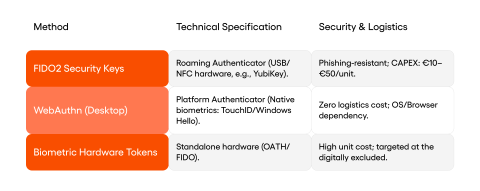

PSD3 states explicitly that payment service providers “shall not make SCA, directly or indirectly, dependent on the possession of a smartphone.” This language appears in the regulatory text reviewed by both EY Belgium and EY Belgium’s PSD3 impact report. Providers must offer at least one SCA method that does not require a smartphone, accounting for elderly users, people with disabilities and the digitally excluded.

This requirement goes far beyond a marginal clause buried in footnotes. It is a serious design challenge that demands financial institutions build a multichannel authentication system. Solutions meeting this requirement fall into three technology categories, each with distinct strengths and limitations.

FIDO2 physical keys (such as YubiKey, Google Titan, Feitian) are the solution with the longest deployment history and the widest ecosystem support. The FIDO2 protocol pairs a cryptographic key stored on a separate hardware device with a user action (a touch, a PIN, or a fingerprint on the key itself). Communication runs over USB, NFC or Bluetooth, with no smartphone required. For banking, FIDO2 offers several concrete advantages: phishing resistance (the key checks the server domain before signing), no shared secrets (no password is transmitted), and compliance with the PSR’s factor independence requirement (key = possession, PIN on key = knowledge, fingerprint on key = inherence). The challenge is distribution cost, ranging from EUR 10 to 50 per key, and user education. Picture a 68 year old bank customer receiving a small metal key in the post with instructions: “Insert into your USB port and touch when the browser asks you to authenticate.” For someone who has always logged in with an SMS code, this is a new mental model, and banks will need onboarding that helps rather than discourages.

WebAuthn through a desktop browser allows authentication using built in biometric readers on laptops (Windows Hello, Touch ID on a MacBook) or platform mechanisms such as passkeys synchronised through the Apple or Google ecosystem. A user without a smartphone can log into online banking on a desktop using the laptop’s fingerprint reader or Windows Hello’s IR camera. For someone who already unlocks their laptop with their face daily, logging into the bank with the same gesture feels natural, and the barrier to entry here is lowest of all three paths. Passkeys, cryptographic keys synchronised through iCloud Keychain or Google Password Manager, open up smartphone free login through a desktop browser, though paradoxically the synchronisation ecosystem itself remains more tightly bound to mobile platforms.

Next generation hardware tokens with displays and biometrics, such as the DIGIPASS FX1 (OneSpan) or Gemalto/Thales hardware tokens, feature a screen showing transaction details for visual verification, a built in fingerprint reader, and offline OTP code generation. They cost more than FIDO2 keys but provide complete independence from any digital ecosystem, which matters most for digitally excluded groups. A customer in a small town using a ten year old desktop can look at the token’s display, see the amount and recipient, press a finger to the reader, and approve the transaction without needing anything else.

SCA architecture after PSD3 comes into force must treat these three paths not as substitutes but as equal authentication channels with a single shared verification backend. An institution that builds SCA solely around a mobile app with SMS as a backup will not meet regulatory requirements, no matter how well the app itself performs.

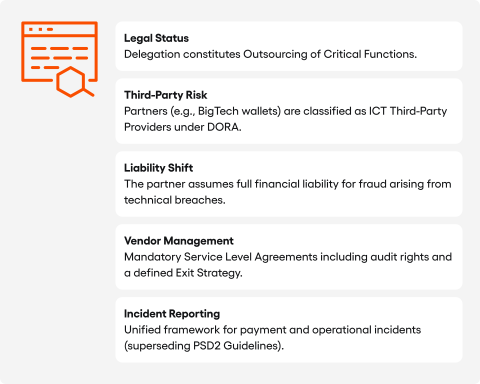

Delegated authentication: who pays when Apple Pay fails?

Article 87 PSR explicitly allows delegated authentication, under which the payer’s PSP permits a third party (a merchant, a payment gateway, or a digital wallet provider) to carry out SCA on the bank’s behalf. This is outsourcing in every sense of the word, triggering EBA Guidelines requirements, due diligence obligations and DORA compliance, as EY Belgium and EY Netherlands describe.

The entire mechanism rests on a shift in liability: the party performing delegated SCA bears the losses from fraud if the authentication fails. To understand what this means, consider a specific scenario.

A customer of Bank X pays for an online purchase through Apple Pay. Bank X has delegated SCA to Apple; Face ID on the iPhone satisfies the authentication requirements. The transaction turns out to be fraudulent: someone unlocked the customer’s device and made the payment. Under PSD3/PSR rules, Apple, as the party that performed delegated SCA, is liable for the loss, not Bank X. The bank must still refund the customer, but has a right of recourse against Apple.

For bank reimbursement budgets, this could prove transformative. If a bank delegates SCA for a significant share of transactions to Apple Pay, Google Pay and large processors (Adyen, Stripe, Worldpay), it shifts a corresponding portion of fraud risk onto those entities. The P&L of delegated authentication becomes a classic “build or buy” decision: the bank weighs the cost of its own SCA system against the cost (presumably higher fees) of delegating to a third party that takes on the risk.

The catch is that delegation does not eliminate risk. It moves risk elsewhere in the value chain. The bank remains responsible for choosing its partner, checking the partner’s SCA mechanisms, and tracking how well they perform. If a partner regularly lets fraud through, the regulator may question the delegation decision itself. The written agreement with audit rights required by the PSR becomes one of the institution’s most important risk documents, as EY Netherlands stresses.

Transaction monitoring as a permanent part of SCA

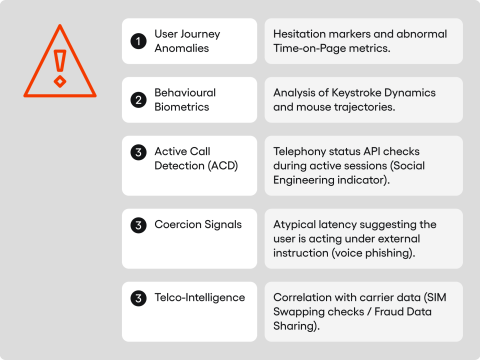

The PSR requires monitoring systems to analyse past payment patterns, environmental and behavioural signals (location, device, spending habits), lists of compromised credentials, signs of malware during sessions, and unusual device activity. Behavioural biometrics and contextual risk scoring are therefore no longer optional add ons. They become regulatory requirements. As EY Netherlands points out, fraud prevention is now tied together with SCA, user education programmes and transaction monitoring into a single integrated system. Treating these elements as separate projects run by separate teams is no longer viable.

SCA exemption rules have been clarified: transaction risk analysis (TRA) keeps its existing thresholds; new dynamic risk based exemptions adjust in real time; trusted beneficiary lists gain greater flexibility, per the regulatory text reviewed by EY Belgium and EY Netherlands. Neither the payer nor the payee bears losses when an SCA exemption has been correctly applied. Device binding requirements favour hardware security modules such as Secure Enclave, TEE and TPM.

Bank impersonation: new liability rules and the role of AI in detecting social engineering

The European Central Bank (ECB) recorded a 17% fall in card fraud after PSD2’s SCA rollout, a clear regulatory success. At the same time, authorised push payment (APP) fraud, where the customer personally authorises a transfer while acting under manipulation, grew by 10 to 11% per year. These trends are documented in EY Global’s analysis of PSD3. McKinsey projects global card fraud losses of USD 400 billion over the coming decade, a figure echoed in its 2025 Global Payments Report. PSD3/PSR takes direct aim at this type of threat, and does so in a way that changes risk management economics in banks from the ground up.

Mandatory refund for bank spoofing, with no cap

The new rules bring in a mechanism that will alter risk calculations across the banking sector: if a fraudster impersonates a bank employee (PSP) and tricks a customer into authorising a payment, the bank must refund the full amount. The condition is that the customer reports the fraud to the police and informs the PSP. Unlike the UK’s APP fraud reimbursement scheme, which caps claims at £85,000 per case, the PSR sets no upper limit. A single high value spoofing case can therefore generate serious, direct balance sheet losses, a point explored in detail by PSP Lab.

The scope of the refund obligation is narrower than in the UK, though: it covers only impersonation of the customer’s own PSP and does not extend to investment scams, romance fraud, or impersonation of police or government agencies. The burden of proof sits with the bank: to refuse a refund, it must show the customer colluded with the fraudster or was grossly negligent. As iPiD notes, the evidentiary bar in spoofing scenarios is now significantly higher than before.

A chain of liability mechanism reaching online platforms is also significant. If a fraud began with a fake social media advertisement, the bank, after refunding the customer, can claim reimbursement from the platform, provided it knew about the fraudulent content and failed to remove it. PwC Netherlands describes this as a direct extension of Digital Services Act principles into payments, signalling that regulators now treat the fraud liability chain as a systemic problem, not a purely banking one.

AI and behavioural biometrics: spotting a customer acting under duress

Mandatory refunds for bank impersonation create a new kind of technological pressure with very concrete economic consequences: it is cheaper for a bank to detect and block a fraud before the customer completes a transfer than to refund the full amount afterwards. In this new calculation, AI driven social engineering detection stops being an innovation. It becomes a defence of the balance sheet.

Traditional antifraud systems analyse the transaction itself: amount, recipient, location, device. They work well against unauthorised fraud (stolen login credentials, for instance). Against authorised fraud, where the customer personally initiates and approves the transfer while being manipulated, these systems are helpless. The transaction looks “normal” across all technical parameters because the customer is the one performing it.

Behavioural biometrics approaches the problem from a different angle. Rather than analysing what the customer does, it analyses how they do it. Signals pointing to someone acting under pressure include: a change in how they move through the app (a customer who normally completes a transfer in 15 seconds suddenly spending 3 minutes on the confirmation screen, or the reverse, an unusually fast flow suggesting phone dictated instructions), deviations from typical typing rhythm, unusual pauses suggesting the person is listening to instructions mid transaction, and unusual circumstances like a large transfer to a new recipient at an odd time from an unfamiliar location.

More advanced systems go further, combining these signals with telecoms data. The PSR creates a legal basis for sharing fraud data between PSPs, and the chain of liability mechanism encourages telecoms providers to cooperate EY Global describes. Imagine: the bank detects that the customer is on a call with a number flagged by the operator as spoofing, at the very moment of the transaction. Combining unusual in app behaviour with a call to a suspect number gives the bank a strong basis for blocking the transaction.

Article 59 PSR (in the Parliament’s amended version) introduces a shared liability model that extends fraud responsibility to electronic communication service providers (ECSPs) and online platforms, a development explored by ThreatMark. For banks, this means building not only their own detection systems but also fraud data sharing platforms, which the PSR explicitly permits as an exception to GDPR restrictions, as EY Global and EY Belgium confirm. This is a rare case where payment regulation and data protection regulation do not stand in conflict but actually complement each other.

The fintech and TPP perspective: how smaller players can turn regulation into an offensive weapon

Industry reports naturally focus on banks (ASPSPs) as the entities carrying the broadest set of obligations. It is worth looking at PSD3/PSR from the perspective of smaller players too, because it is precisely for them that the new rules may prove most beneficial.

API equality as a leveller

Killing the fallback interface and requiring dedicated APIs to match the bank’s customer facing interface is the single biggest regulatory gift to fintechs since PSD2. Under PSD2, banks routinely built technical barriers against TPP access: extra authentication steps, deliberately slowed dedicated interfaces, incomplete API responses. The fallback was meant to prevent this but ended up adding complexity for TPPs.

PSD3/PSR closes the gap from two sides at once. First, the dedicated interface must perform as well as the customer interface, a requirement that is measurable and enforceable, as EY Belgium and Accenture confirm. Second, the PSR contains an explicit list of prohibited obstacles to data access, closing the grey areas banks previously used to undermine TPP access.

The implications for the market run deep. Ambitious fintechs (Revolut, Wise, Tink, or data aggregators like Plaid) gain the ability to build products delivering a better experience than the bank’s own app, using the same real time data. An aggregator combining current account, credit card, savings and investment portfolio data (within FIDA’s scope) in a single dashboard could become the customer’s primary financial interface, pushing the bank into an infrastructure role.

Direct access to payment systems

The right for nonbank PSPs to participate directly in EU payment systems, documented by Deloitte Luxembourg and PwC Netherlands, could reshape the market more deeply than any API rule. Until now, fintechs relied on sponsor banks to settle transactions, a dependency that gave banks a veto over fintech business models, control over settlement pricing, and visibility into competitors’ volumes.

Once a fintech can participate in TARGET2 or STEP2 on its own, the strongest monopolistic hold banks have in the payments value chain falls away. A survey by EY Global found that 67% of banks believe PSD3 will encourage new market entrants. Given the scale of changes in access to settlement infrastructure, this is probably an underestimate of the competition ahead.

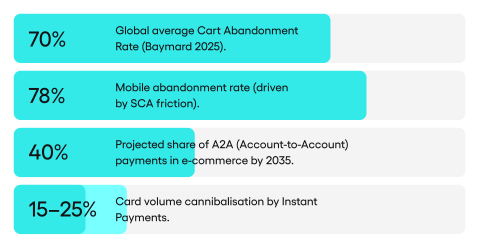

Ecommerce under the microscope: abandoned baskets, delegated SCA and the future of one click payments

The problem: SCA versus conversion

A customer is browsing an online shop on their phone while riding a tram. They have picked shoes, added them to the basket, typed in a delivery address. They tap “Pay”, and a sequence begins that ends in abandonment for many: redirect to the bank’s site, enter a password, wait for an SMS code, type it in, return to the shop, reload the page. The tram enters a tunnel, the connection drops, the session expires. The shoes stay in the basket.

This is not a made up scenario. The average global cart abandonment rate in ecommerce sits around 70% (Baymard Institute, 2025), and on mobile devices it reaches 78%. A complicated checkout process and multistep authentication requirements are among the main causes. Microsoft found in testing that SCA leads to a meaningful rise in purchase abandonment across European ecommerce. A full 22% of buyers abandon a purchase because the payment process is too long or too complicated, meaning one in five customers who reached the payment stage and intended to buy walks away at the very moment they should be paying.

The answer: delegated authentication as the foundation for a frictionless checkout

PSD3/PSR gives merchants a way out of this bind. Delegated authentication (Article 87 PSR) allows a large payment processor (Adyen, Stripe, Checkout.com) to take over SCA from the card issuing bank, as EY Belgium and EY Netherlands explain. The merchant or processor can then authenticate the customer using device biometrics (Face ID, fingerprint), a tokenised card in a digital wallet, or a passkey, with no redirect to the bank’s website, no SMS OTP, no extra steps breaking up the purchase flow.

Back to the customer on the tram. Under delegated SCA the same purchase looks different: tap “Pay,” press a finger to the phone’s reader, transaction approved. One touch instead of five steps. A customer with a saved card in a digital wallet who authenticates biometrically completes the purchase in a single gesture, getting close to the ideal of “one click payment”, but with full regulatory compliance. Extended TRA exemptions in the PSR allow SCA to be skipped for low risk transactions from known customers, as the EY Belgium review confirms, further reducing friction between purchase intent and actual payment.

Celent estimates that A2A (account to account) payments will grow from 24% to nearly 40% of ecommerce by 2035 on major European markets. Capgemini forecasts that instant A2A payments will absorb 15 to 25% of future card transaction volume growth. The scale of this shift (A2A’s share nearly doubling in a decade) means ecommerce is undergoing a structural change in payment channels. Delegated SCA and extended exemptions could speed this transition, provided payment processors build a purchase experience that simultaneously meets PSR requirements and reduces basket abandonment.

The risk: who is liable for fraud under the delegated model?

For merchants, the risk is that payment processors, by taking on SCA liability, may pass the cost of higher fraud risk through to fees. A merchant using delegated SCA through Adyen might pay a higher interchange or processing fee to compensate Adyen for carrying fraud liability under the delegated model. On the other hand, less friction in the payment process should lift conversion, and the net effect depends on the balance between sales growth and fee increases. This is a calculation every merchant will need to run individually, factoring in customer risk profiles and average basket value.

DORA and cybersecurity: the regulatory web where PSD3 does not exist in a vacuum

PSD3/PSR does not operate in isolation from other regulations. The Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), fully applicable from 17 January 2025, creates a parallel set of requirements that directly affects how payment systems are built, as the EBA has outlined.

PSD3 + DORA synergy: two sets of requirements, one technology stack

DORA covers five areas of ICT security (ICT risk management, incident reporting, digital resilience testing, ICT third party risk management and information sharing), as EIOPA details, while PSD3/PSR imposes on the same entities the obligations of real time transaction monitoring, fraud data sharing between PSPs, and management of delegated authentication mechanisms.

Both sets of rules must be delivered on the same technology stack, by the same teams, within the same budget. IT teams building SCA and fraud monitoring systems under the PSR must simultaneously meet DORA’s incident reporting requirements. A major ICT incident (a breach of the SCA system, a credential leak, or a DDoS attack on API infrastructure) must be reported to the relevant national authority within hours per DORA’s timetable. The EBA has repealed its PSD2 Guidelines on incident reporting, moving these obligations under DORA. A single reporting window now covers both operational and payment related incidents.

For IT teams, three implementation priorities emerge. Transaction monitoring built under the PSR should from the start generate logs and alerts compatible with DORA incident reporting, not as an add on but as a base architectural element. Delegated authentication infrastructure falls under DORA’s ICT third party risk rules, since a partner performing delegated SCA is an ICT provider in DORA’s terms. Penetration testing and TLPT, required by DORA for high risk institutions, should cover SCA system breaches and open banking API scenarios, as Partisia recommends.

The PSR classifies delegated authentication as outsourcing, per the EY Netherlands review, triggering both EBA outsourcing Guidelines and DORA’s ICT third party risk requirements. The chain of consequences reaches far: an institution delegating SCA to Apple Pay must treat Apple as a critical ICT provider. This means maintaining a register, conducting due diligence, holding audit rights, keeping exit plans and arranging business continuity for an Apple outage, as both EY Netherlands and EIOPA stipulate. For many banks, negotiating audit terms with a company whose market capitalisation exceeds the GDP of several European nations will be an entirely unfamiliar experience.

The quantitative landscape: numbers that show the scale of change

Market scale: global payments revenue reached USD 2.5 trillion in 2024, forecast to hit USD 3.0 trillion by 2029 at 4% CAGR, according to McKinsey’s 2025 Global Payments Report. Half a trillion dollars of growth in five years means every percentage point of market share is worth more than yesterday, and regulation decides who captures it. Cashless transactions will grow from 1.4 trillion (2023) to 2.8 trillion (2028) at 15% CAGR. In Europe, the figure is 361 billion, per Capgemini. Doubling volumes in five years while regulations simultaneously shift means infrastructure must grow faster than the traffic it handles. EU instant payments are set to rise from 3 billion to around 30 billion transactions by 2028, representing 50% annual growth, as McKinsey noted. A tenfold jump in settlement system load over five years makes the scalability question very real.

Open banking adoption: 64 million users in Europe in 2024 represent just 25% of banking customers, the EY bank readiness survey shows. Three quarters of the market remain untouched, pointing to enormous growth potential and to the fact that PSD2 has not yet convinced most consumers. Forrester forecasts a doubling by 2027. Open banking API calls will rise from 137 billion (2025) to 720 billion (2029), up 427%, per Capgemini. Banks building PSD3 dedicated interfaces today must design for loads that at launch will be only a fraction of eventual traffic.

Fraud economics: McKinsey estimates USD 400 billion in card fraud losses over the coming decade, more than Austria’s annual GDP. APP fraud grows at 11% per year (CAGR 2023 to 2027), according to EY Global. European losses reached EUR 1.55 billion in 2020. PSD2 SCA delivered a 17% drop in card fraud, a clear win, but new forms of authorised fraud are growing faster than old forms are shrinking. The gap keeps widening.

Fintech ecosystem: BCG and QED Investors project fintech revenues of USD 1.5 trillion by 2030, and PSD3/PSR opens doors for new players to enter markets previously reserved for banks. CB Insights recorded European fintech funding at USD 7.6 billion in 2024, signalling capital’s return after two years of decline. The embedded finance market grows from USD 185 billion (2024) to a projected USD 320 billion by 2030, per BCG. Near doubling in six years means financial services will increasingly appear where customers are not looking for them: inside shopping platforms, loyalty apps and business software.

Conclusion: coming months that will define the next decade of payments

PSD3/PSR is not a routine compliance exercise. It is an architectural reset for European payments. The package solves PSD2’s fragmentation problem through a directly applicable regulation, while expanding mobile banking app requirements to a degree unmatched by the previous regime, as analyses by Deloitte Luxembourg, Deloitte UK and EY Belgium confirm: multichannel SCA independent of smartphones, consent management dashboards, performant APIs, behavioural fraud monitoring and readiness for FIDA.

Delegated authentication with liability shift, mandatory refunds for bank impersonation, removal of the fallback mechanism, Verification of Payee for all transfers; each of these changes individually requires rebuilding backends and authentication stacks. DORA adds an operational resilience layer that must be designed in from the start; not bolted on afterwards as an overlay on existing systems.

With 70% of senior management insufficiently informed and just 44% of institutions considering themselves ready, the EY bank readiness survey shows, the window for getting ahead is closing with each passing quarter. BCG’s estimate: EUR 2.2 to 2.4 billion in costs against EUR 4.6 to 12.4 billion in potential gains; spells out the economic logic clearly.

These numbers are worth reading from a different angle, though. PSD3/PSR does not so much impose costs as force a strategic choice: does the institution want to be the infrastructure others build on, or the platform that defines the customer experience? Banks that treat regulation as a chance to rebuild their technology stack and customer relationships will be in a very different position in five years compared with those that settle for meeting minimum requirements. The difference between these two paths comes down not to budget size but to whether the board sees PSD3 as an invoice to pay or an architectural plan to carry out.

Institutions that treat PSD3/PSR as an opportunity to reshape their digital offering will come out with a stronger market position. Those that treat it purely as a cost centre risk joining the 62% unprepared for open finance, as Capgemini documents, and a gradual slide into the role of infrastructure provider for more agile competitors.

Eighteen months from formal adoption is less time than it sounds. Especially when 59% of banks are still battling outdated systems, as Accenture found, and every quarter of delay means less time for work whose scope is not shrinking.

How do PSD3 and the PSR reshape EU payment markets and payment services?

The Payment Services Directive 3 (PSD3) and the Payment Services Regulation (PSR) introduce a unified legal framework for EU payment markets. By moving from a Directive to a directly applicable Regulation, the rules eliminate divergent national interpretations. This “architectural reset” mandates identical payment services standards across the Union, requiring payment service providers to rebuild authentication systems and ensuring a level playing field for banks and non-bank players.

What new fraud prevention mechanisms protect electronic payments?

To combat rising fraud, the regulation mandates appropriate fraud prevention mechanisms for all electronic payments. Payment service providers must implement “Verification of Payee” to match account names for credit transfers and electronic money services. Additionally, transaction monitoring must analyze behavioral signals to detect manipulation. Consumer protection is strengthened by requiring full refunds if a fraudster impersonates a bank employee (bank impersonation).

How does the regulation impact open banking and payment service providers (PSPs)?

Open banking reforms require payment service providers (PSPs) to offer dedicated interfaces for data sharing that perform as reliably as customer-facing apps. Account information service providers gain clearer access rights, while banks must provide a “permission dashboard” for users to manage data access. Under Financial Data Access (FIDA) rules, this extends to mortgages and pensions, forcing financial institutions to adopt microservices architectures.

What rules apply to financial institutions regarding payment security?

Financial institutions must upgrade payment security by ensuring Strong Customer Authentication (SCA) is not dependent solely on a smartphone. To support payment service users who are digitally excluded, payment service providers must offer alternative methods like FIDO2 keys or desktop biometrics. This ensures a secure payments ecosystem where payment services remain accessible and secure for everyone.

How do the directives improve consumer protection for cross border payments?

Consumer protection for cross border payments is enhanced through stricter liability rules. If a payment service provider delegates authentication to a third party (like a digital wallet), the third party bears the liability for fraud. Furthermore, payment services must provide human customer support and transparent currency conversion charges, ensuring that payment service users are treated fairly across the Single Euro Payments Area.

What are the payment services obligations for fraud prevention?

Payment services must integrate fraud prevention directly into their technical infrastructure. The Payment Services Regulation requires payment service providers to share fraud data with each other to detect complex scams. This collaboration helps identify payment fraud patterns, such as social engineering, in real-time. Payment systems must now block transactions where payment account data suggests the user is acting under duress.

How does the political agreement on Payment Services Directive 3 address fraud and liability?

The political agreement underpinning Payment Services Directive 3 and the new Payment Services Regulation seeks to combat payment fraud by ensuring reimbursed defrauded customers are protected. In specific cases electronic communications providers may now share liability for spoofing. This forces bank payment service providers to implement stricter security measures and risk assessment protocols to prevent regulatory arbitrage.

How will the new rules harmonise payment services for non-bank providers?

The regulations aim to harmonise payment services and foster more efficient payment processes by allowing non bank payment service entities to directly access payment account data and settlement systems. This helps provide payment institutions and authorised open banking providers with a level playing field, upgrading user interfaces for open banking services and defining the payment services provided under the payment services regulation psr.

This blog post was created by our team of experts specialising in AI Governance, Web Development, Mobile Development, Technical Consultancy, and Digital Product Design. Our goal is to provide educational value and insights without marketing intent.