FiDA: what it is and why it matters

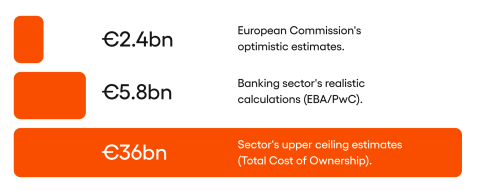

€36 billion – that’s the sector’s estimate for what European institutions might spend implementing the FiDA regulation. Five times more than PSD2 costs, definitively ending the era of free data transfer and forcing boards to shift from regulatory defence to aggressive API monetisation. Any organisation failing to build its own data-sharing scheme within the next 24 months will be relegated to invisible infrastructure provider for Big Tech and crypto platforms.

Table of contents

Key takeaways

- €36 billion: upper limit of implementation costs for the EU sector – an outlay five times greater than PSD2.

- End of “free data”: FiDA introduces a market-based fee model for API calls, transforming IT departments from cost centres into revenue units.

- Window of opportunity (2026–2027): only during this window can institutions genuinely influence the shape of FDSS schemes; passivity means accepting standards imposed by competitors.

- €48 billion: estimated value of the additional Open Finance market in the EU by 2030 – most of this sum will go to interface controllers, not data holders.

- MiCA integration: cryptocurrency exchanges enter the game as data holders and FISPs, enabling them to aggressively offer traditional loans and deposits.

- Scoring in 5 minutes: in the B2B segment, automatic of data from ERP, banking and e-commerce systems eliminates manual credit risk analysis.

- EUDI Wallet: the EU digital identity wallet will reduce onboarding abandonment rates by 40% through elimination of cumbersome redirects.

Evolution from PSD2 to the era of open finance

The financial sector in the European Union stands at the threshold of a second wave of digital regulatory transformation. The effects will run deeper than anything we’ve seen so far. The PSD2 directive (Payment Services Directive 2) opened access to payment accounts, thereby creating the foundations for Open Banking. The FiDA initiative (Financial Data Access) goes further – extending this model to nearly all financial products, creating a regulatory framework for Open Finance.

Political and economic context

The European Commission was pursuing its Digital Finance Strategy and conducted an analysis of the European financial market. The diagnosis was clear: lack of data access forms a barrier to innovation in the sector. The problem turned out to lie in the structure of the current system. Customer data remains locked in information silos belonging to individual institutions – each bank, each insurer and each investment fund processes customer data but doesn’t share it with external entities. As a result, the market stands still. Competition gets limited to players already present in the market, whilst the creation of personalised financial products based on analysis of a customer’s financial situation remains in the realm of dreams.

FiDA is the response to these challenges. The regulation aims to create a single financial data market across the entire European Union, where such data can flow freely between institutions – with customer consent, naturally. This concept rests on shifting the centre of gravity: data belongs to the customer, not to the institution processing it. Customers should therefore decide who can use information about their finances and for what purpose.

Legislators have drawn lessons from PSD2’s implementation shortcomings, though. That regulation, whilst innovative in principle, encountered a series of problems in practice. The main issues were lack of technical standards, API interface quality, and above all the absence of balanced business models for banks forced to provide infrastructure free of charge. As outlined by the European Commission, FiDA takes a more measured approach – legislators propose basing the system on market schemes and introduce the possibility of charging fees for infrastructure, which should guarantee economic stability for the entire ecosystem.

Strategic requirement for boards

For boards of financial institutions, FiDA means the need to redefine their operating model. This cannot be treated as just another compliance project. FiDA is a structural change that will affect every aspect of how an organisation functions.

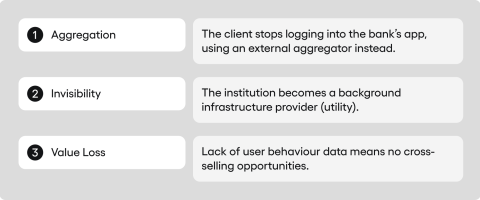

Revenue models will change. The profit sources for financial institutions – interest margins and transaction fees – will gradually lose significance. The future belongs to revenues generated from data-based services and operating within financial ecosystems. Institutions that can effectively monetise data access (as data holders) or build value based on aggregated information from multiple sources (as financial information service providers) will outpace their competitors. Those remaining in the old model will gradually become merely infrastructure for other players.

We can see clearly that what’s at stake is the customer relationship. FiDA creates genuine risk of losing the point of contact (interface) with users to aggregators and technology platforms. The scenario is straightforward: customers stop logging into their bank, insurer or investment fund applications. Instead, they use one central platform – an aggregator that shows their entire finances in one place: all accounts, all policies and all investments. The financial institution then becomes just a product provider operating in the background, invisible to the customer. The opportunity to sell additional services vanishes. Data about user behaviour vanishes along with it. What remains is worse – the institution loses the foundation for building loyalty.

The transformation forces a rebuild of IT architecture. Building efficient, secure API interfaces is essential for systems that historically weren’t designed to work in real time at all. This will be particularly painful for the insurance sector, where legacy systems – often decades old, rooted in mainframe architecture – will suddenly need to handle hundreds of thousands of API queries daily. Modernisation costs for major market players run into hundreds of millions of euros.

Architecture: definitions and scope

Precise understanding of FiDA’s conceptual framework is essential for properly assessing the regulation’s impact on an organisation. The regulation introduces new categories of entities and obligations that differ from the constructions known from PSD2.

New market classification

Financial Information Service Provider (FISP)

The definition reads as follows: a FISP is an entity that has obtained regulatory authorisation to access a customer’s financial data for the purpose of providing information services. The range of possible services is broad – from simple aggregation of data from multiple sources (showing customers all their accounts in one place), through advanced financial analytics (investment portfolio optimisation), to new products based on full insight into a customer’s financial situation, where creditworthiness assessment takes into account income, obligations and assets.

The implications of this definition reach further than might seem apparent. Unlike TPPs (Third Party Providers) under PSD2, FISP status isn’t reserved exclusively for fintechs and new technology market entrants. As explained in resources from Stripe, banks, insurance companies or investment funds wanting to retrieve data from competitors – for example to assess creditworthiness taking into account obligations at other banks, or to personalise an insurance offer based on a complete asset profile – must also operate in the FISP role. What does this mean in practice? Most large financial institutions will operate in a dual role: as data holders (sharing customer data with other entities) and as FISPs (retrieving data from competitors).

Licensing forms a barrier to entry here and gives regulated players a competency advantage. Obtaining FISP status requires authorisation by the appropriate supervisory authority – in Poland, by the Financial Supervision Authority. This process involves meeting a series of requirements concerning operational security, cyber risk management, governance and personal data protection. For startups and small fintechs, this is quite a high entry threshold – it requires resources on the compliance and security side. Analysis by PwC notes that institutions already licensed as banks, insurance undertakings or investment firms can use a simplified notification pathway, giving them a time advantage over new players. They can start operating as FISPs faster, with lower administrative costs, which in a dynamic market can determine positioning.

Data Holder

The other side of the coin. An institution obliged to share data on demand from a customer who has granted consent to an entity operating as a FISP.

Unlike the PSD2 directive, which concentrated exclusively on institutions maintaining payment accounts (so-called ASPSPs – Account Servicing Payment Service Providers), the FiDA regulation introduces a significantly broader scope, encompassing nearly all financial market segments.

According to the definition of “data holder” in FiDA, the regulations cover:

- Credit institutions: commercial, cooperative and mortgage banks.

- Insurance undertakings: with exclusion of certain particularly sensitive risk categories (discussed later).

- Investment firms: including brokerage houses and investment advisors.

- Pension institutions: entities running occupational pension schemes (PPE) and employee capital plans (PPK).

- Crypto-asset service providers (CASPs): a category introduced by the MiCA regulation.

- Other entities: As Stripe details, credit intermediaries and electronic money issuers are also included.

Each of these institutions will need to build technical infrastructure enabling data sharing in real time through standard API interfaces. Whilst simultaneously ensuring these interfaces are available for at least 99.5% of the time (SLA requirements will be specified in technical standards) and securing them according to the highest cybersecurity standards. For a medium-sized institution, we’re talking about a project worth tens of millions of euros spread over several years.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) operating as financial institutions have been excluded from data holder obligations. Legislators decided that burdening them with disproportionate technological costs could threaten profitability and ability to compete in the market. The exclusion is optional – SMEs can voluntarily join the system if they believe it will bring them business benefits, but they’re not obliged to do so.

Data User

The third category is data user – any entity that obtains legal access to customer data with consent. In practice, every FISP is a data user, but this category emphasises the functional perspective: the role of consuming information in the entire value chain.

FiDA imposes strict obligations on data users regarding purpose limitation. They can be used in accordance with consent expressed by the customer. If they agreed, for instance, to share data for creditworthiness assessment purposes, this data cannot be used to send marketing offers for other products. If a customer gave consent for account aggregation in a household budget management app, the data user cannot exploit this information to build consumer profiles for other entities.

Stripe highlights that FiDA introduces a ban on “stockpiling” data (data hoarding). Data users cannot retrieve more data than is necessary to achieve the agreed purpose, nor store it longer than required. This represents a change from many current practices, where technology platforms often retrieve the maximum scope of data “just in case”, building databases about users’ financial behaviours. Violation of these principles will involve administrative penalties – in line with GDPR rules, up to 4% of global turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher.

Subject matter scope of data

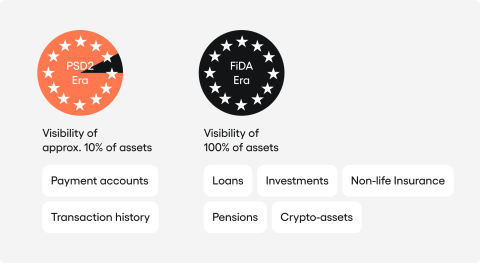

FiDA defines “customer data” very broadly, encompassing information related to a wide spectrum of financial services. This is no longer just about current account balances and transaction lists, as with PSD2. The scope extends far beyond banking.

Data covered by the regulation:

- Credit: we’re talking about the full spectrum of data concerning all types of credit – mortgages, consumer loans, credit lines, credit cards, car finance and consolidation loans. Data includes current debt balance, detailed contract terms (interest rate, repayment schedule, additional clauses), complete repayment history showing whether the customer always paid on time or whether delays occurred. Information about security (mortgages, pledges) and data about the application process and creditworthiness assessment are added. The aim is to enable other entities to build a complete picture of a customer’s credit burden – which is essential for responsible lending.

- Savings and investments: this category encompasses all forms of capital accumulation and investing. Savings accounts with interest rates and conditions for accessing funds. Term deposits with amount, maturity date, interest rate and early termination conditions. Financial instruments held in brokerage accounts – shares, bonds, certificates and warrants – with details of quantity, acquisition value and current market value. Units in investment funds, where information will be available on fund types, unit values, performance history and management costs. Access to this data will allow financial advisors and robo-advisors to optimise a customer’s investment portfolio, taking into account all assets regardless of which institutions hold them.

- Insurance: this segment stirred emotions during legislative work. FiDA’s scope covers Non-Life insurance policies – motor insurance (third party, comprehensive, personal accident), home and property insurance (fire, flood, theft), liability insurance and travel insurance. Data includes policy details: scope of cover, premium amount and period of validity. Claims history showing when and what claims were reported and how they were settled. Loss ratio for the customer. Access to this information will enable insurance comparison sites and competing insurers to present personalised offers based on a customer’s actual history, not just on declarations.

- Pensions: FiDA covers pension products from voluntary pillars of pension provision – Individual Retirement Accounts (IKE), Individual Retirement Security Accounts (IKZE), Employee Pension Schemes (PPE) and Employee Capital Plans (PPK). Data includes accumulated capital, contribution history, investment structure, management fees and projected benefit amounts. State pay-as-you-go systems like ZUS or KRUS have been excluded from FiDA’s scope – they remain outside the regulation because they’re not financial products but mandatory social insurance systems.

- Crypto-assets: a new category that didn’t exist in PSD2. FiDA integrates with the MiCA regulation (Markets in Crypto-Assets), which regulates the cryptocurrency market in the European Union. As BNP Paribas Securities Services indicates, this covers information stored by crypto-asset service providers (CASPs) which will need to be shared on the same terms as financial institution data. This covers information about held crypto-assets (type, quantity, acquisition value, current market value), transaction history (purchase, sale, exchange between currencies), staking and other forms of generating returns from crypto-assets. A significant solution that effectively recognises crypto-assets as a full part of EU citizens’ personal finances.

- Capacity assessment: the final category is technical and controversial. FiDA obliges financial institutions to share input data used for assessing a customer’s creditworthiness. This means all information the institution took into account when making decisions – customer income including sources and stability, financial obligations covering other loans or maintenance payments, employment data, information about owned assets and credit scoring assigned by the institution. What’s significant is what FiDA doesn’t require sharing: scoring algorithms and institutional know-how. The scoring model, weights of individual variables and decision thresholds – all this remains the institution’s trade secret. Only input data and the decision (credit granted/refused) are shared, but not the processing mechanism that led to that decision.

Exclusions (red lines):

Following negotiations and lobbying, sensitive data concerning life insurance, health insurance and sickness insurance has been excluded from FiDA’s scope. This decision resulted from two parallel political processes.

The insurance sector, represented by the organisation Insurance Europe, conducted a lobbying campaign arguing that opening access to customers’ medical and health data could lead to discriminatory risk profiling. The scenario runs as follows: a competing insurer or fintech obtains access to a customer’s complete health history, including detailed information about past illnesses, medications taken, test results and hospitalisation records. Based on this, they build a precise medical risk profile allowing them to offer very attractive terms to “healthy” customers – low premiums and broad cover. Simultaneously excluding or raising prices for customers with health problems. The result would be market segmentation where people with health issues would struggle to find affordably priced policies.

Data protection authorities – particularly the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) – warned against violating privacy principles in such sensitive areas as health and private life. Legal experts at Hogan Lovells note that medical data falls into the category of special categories of data under GDPR and requires a high level of protection. The risk of leakage, improper use or profiling based on this data was deemed too high relative to the potential benefits of sharing it.

Consequently, life, health and sickness insurance remains outside FiDA’s scope. Customers won’t be able to instruct that data from their health policy be shared with an aggregator or competing insurer, even if they wanted to. This is one of the few situations where legislators decided that a customer’s right to control their data must give way to the principle of protection against discrimination and the right to privacy in the health domain.

Comparative analysis: PSD2/3 vs. FiDA

From a management perspective, understanding the difference is vital: FiDA isn’t a simple extrapolation of PSD2. The regulation introduces changes to the economic and operational model designed to fix errors in previous provisions – errors that have generated high costs for financial institutions over recent years without return in the form of business benefits.

Analysis area: data scope

- PSD2 / PSD3 (Open Banking): narrow scope limited exclusively to payment accounts – transaction history, balance and list of transfer beneficiaries constitute a small slice of a customer’s financial life.

- FiDA (Open Finance): complete picture of wealth encompassing portfolio of assets and liabilities, insurance policies, investment portfolios and crypto-assets. Transition from fragmented view to financial panorama.

- Implications for management: ability to build a 360° customer profile. In practice, this means moving from simple transactional services – handling transfers and payments – to holistic advice taking into account the entirety of one’s financial situation. Banks stop being places for storing money, becoming financial partners instead.

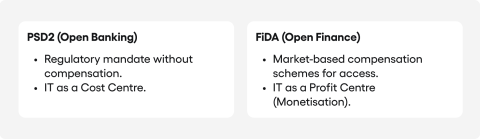

Analysis area: economic model

- PSD2 / PSD3 (Open Banking): free mandate imposed top-down by the regulator. Ban on charging any fees to payment service providers (TPPs) for data access. The cost of building and maintaining API infrastructure rested solely with banks without any compensation.

- FiDA (Open Finance): market compensation determined by participants. Ability to charge “reasonable” fees to data users within FDSS schemes (Financial Data Sharing Schemes). Finally, a cost recovery mechanism.

- Implications for management: transformation of the IT department from a cost centre consuming budget into a profit centre generating value through API monetisation. The change requires strategy revision – from perceiving APIs as a regulatory necessity to treating them as a business product.

Analysis area: standardisation

- PSD2 / PSD3 (Open Banking): regulatory standardisation imposed by RTS (Regulatory Technical Standards). Technical standards specified top-down by the European Banking Authority (EBA), implemented in fragmented fashion. The result: different API standards in different countries generating additional integration costs for entities operating cross-border.

- FiDA (Open Finance): market standardisation developed bottom-up within FDSS. Standards set by market participants themselves in data-sharing schemes, not imposed by the regulator. A more pragmatic and flexible approach.

- Implications for management: necessity of participating in scheme work from the very start. An institution remaining passive allows competitors to set standards that might prove unfavourable to its infrastructure and generate disproportionately high adaptation costs. Early engagement represents an investment allowing influence over the shape of future rules of the game.

Analysis area: consent management

- PSD2 / PSD3 (Open Banking): consent granted directly to payment service providers (TPPs), then verified by banks through authentication mechanism (SCA). The system had a flaw – consents scattered across many external platforms, and customers had no single place to check active consents and revoke them.

- FiDA (Open Finance): mandatory permission dashboards. Every data holder must provide customers with a panel managing all granted consents in real time – information about who has access to what data, when consent expires, and the ability to withdraw immediately.

- Implications for management: greater transparency theoretically strengthens customer trust. Simultaneously, the risk of “mass consent withdrawal” (churn) emerges. Situation: a customer logs into the dashboard and sees a list of ten different entities having data access. User experience (UX) poorly designed – convoluted interface, unclear descriptions – leads to the reflex “withdraw everything” out of privacy concerns. The institution might lose access to data consciously shared by the customer in the past. Care for intuitive, user-friendly dashboard design stops being a matter of aesthetics, becoming a business requirement instead.

Analysis area: transaction initiation

- PSD2 / PSD3 (Open Banking): PIS (Payment Initiation Service) – ability to order transfers directly through external providers. Fintechs could not only read a customer’s balance but also initiate a transfer from their account after obtaining consent and passing authentication.

- FiDA (Open Finance): read access only. The current draft regulation doesn’t provide for a “transaction initiation” mechanism through API interfaces – for example, purchasing investment fund units or submitting insurance instructions. The regulation focuses exclusively on information access, not on executing operations.

- Implications for management: consequences. First – lower operational risk, especially in the fraud area. No ability to execute transactions means that potential attack or error in an external system won’t lead to uncontrolled outflow of funds or conclusion of unauthorised contracts. Second – limitation of transactional potential for fintechs in the first implementation stage. Technology firms must build added value exclusively based on aggregation and data analysis, not facilitating transactions themselves.

Analysis area: entities and market roles

- PSD2 / PSD3 (Open Banking): asymmetric division of roles – TPPs (Third Party Providers) splitting into AISPs (Account Information Service Providers) and PISPs (Payment Initiation Service Providers), and ASPSPs (Account Servicing Payment Service Providers), essentially banks. Banks were exclusively “data givers”, fintechs exclusively “data takers”.

- FiDA (Open Finance): introduction of the concept of FISP (Financial Information Service Provider), which can be any financial institution, including banks. The same organisation can appear simultaneously as Data Holder for some products and Data User for others. Market symmetrisation.

- Implications for management: increased symmetry means a significant strategy shift. Every institution becomes simultaneously data giver and taker. A bank that previously only reluctantly shared customer data with competitors can now aggregate data from other institutions itself, building its own value-added services. Transition from defensive posture (“how to protect our data”) to offensive posture (“how to exploit competitors’ data to enrich our products”).

Market vs. regulatory model – the difference

A significant change between PSD2 and FiDA lies in moving away from the “free access” model that generated frustration in the banking sector over recent years.

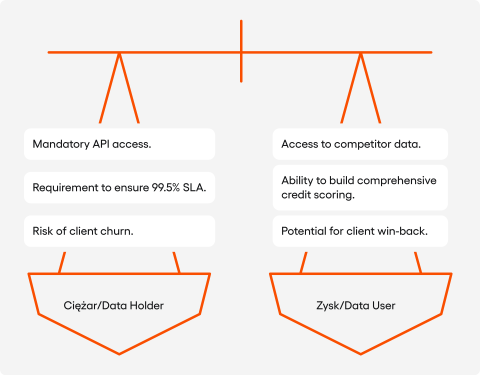

In the PSD2 era, banks bore high costs of building API infrastructure – millions of euros on system modernisation, hiring development teams, testing, certifications and ensuring 24/7 availability. Fintechs primarily benefited from this infrastructure, without participating in maintenance costs. As more fintechs used APIs, banks’ operating costs grew (greater server load, technical support costs, expansion of monitoring teams), but revenues remained zero. Asymmetry: one entity bears costs, another reaps benefits.

FiDA introduces a market mechanism where data holders have the right to compensation for providing resources. The model change aims to encourage institutions to build high-quality interfaces – so-called Premium APIs characterised by high availability (SLA at 99.9% level), richer data sets than the regulatory minimum, and better technical documentation. Interfaces generate revenue, so an institution investing in surplus quality can charge higher fees. A report by the Euro Banking Association suggests the market mechanism leads to improved standards across the entire ecosystem.

Analysis of costs and revenues: FiDA economics

Implementing FiDA involves a temporal asymmetry in cash flows that poses challenges for financial planning. Capital expenditure (CAPEX) is obligatory – it must be incurred now to meet regulatory requirements before the regulation comes into force. Revenue streams are potential and distant in time, dependent on the adopted business strategy, market maturity and how quickly customers start using services based on open data. We pay high amounts today, we earn perhaps tomorrow.

Implementation cost estimates

Significant divergence exists in cost estimates between the European legislator and the market sector. The divergence represents a budgetary risk for institutions planning implementation based on European Commission forecasts, which may prove significantly underestimated.

European Commission perspective:

In the official Impact Assessment, the Commission estimates one-off implementation costs for the entire EU financial sector at €2.2bn – €2.4bn, averaging a few million euros per institution. Annual operating costs (OPEX) related to maintaining the system should range from €147m to €465m across the entire EU. According to the Commission, administrative costs will be relatively low thanks to experience gained during PSD2 implementation – the argument: “we’ve already done this, so now it will be easier and cheaper”. Legal analysis by Eris Law critiques the logic, noting it doesn’t account for differences in scope and depth of changes.

Banking sector perspective (realistic):

Independent industry analyses, supported by detailed reports from advisory houses (including PwC, Deloitte) and official positions from the European Banking Authority (EBA), indicate significant underestimation of costs by the European Commission.

The banking sector estimates costs closer to €5.77bn across the entire European Union – more than double what the Commission assumes. The difference arises because the Commission relies on theoretical models and extrapolation from PSD2, whilst banks base estimates on actual historical costs and detailed technical analyses of necessary actions.

For a single medium-sized bank (Mid-Tier), the cost of full FiDA compliance is estimated at €90–100m. The amount covers not just programming work but the entire range of activities: infrastructure modernisation, system building, testing, training, legal adjustments and costs of participating in schemes.

For large capital groups (Tier 1) operating in multiple countries and offering the full range of financial products, costs may exceed €150m. This results from legacy system complexity – large, old, extensive IT platforms accumulated over decades – and the need to integrate data from many different legal jurisdictions and product lines (retail banking, private banking, asset management, insurance and leasing). Data from the European Central Bank confirms that for large capital groups, costs may be substantial.

Cost centres (cost drivers):

- Legacy system modernisation: the largest cost area. Unlike payment systems operating in 24/7 transactional mode (every payment processed immediately), systems handling other financial products often operate in batch processing architecture. Mortgages are processed once daily in overnight batches, insurance policies update once weekly, and investment portfolios recalculate valuations after market close. Systems were designed decades ago on the assumption that data needn’t be available in real time. FiDA requires all data to be shared on demand, practically instantly. Adapting batch systems to real-time access requirements demands rebuilding the entire technical architecture. Consultants at Deloitte observe that often it proves easier and cheaper to build an intermediary layer (middleware) than rebuild core systems – but even that costs tens of millions.

- Permission dashboards: building a consent repository integrating with systems handling dozens of products represents an engineering and legal challenge. Consents must be tracked granularly – information that “customer X shared data with company Y” isn’t enough. One must know: which data (account, loan, investments?), in what scope (balance, history, documents?), for how long and with what limitations. Everything must then be shown to customers in an understandable and intuitive way. This requires creating databases, user interfaces, integration with authorisation systems and mechanisms for automatically expiring consents after the deadline. Further analysis by Deloitte Luxembourg emphasizes that each element generates costs.

- Participation in data-sharing schemes (FDSS): joining a scheme itself involves costs – membership fees, legal costs related to negotiating terms, and operational costs related to adapting technical infrastructure to standards adopted by the scheme. Each country or region may have its own scheme, so an institution operating in multiple countries must participate in several schemes simultaneously, which multiplies costs.

Revenue models and Premium APIs

Despite high initial costs, FiDA opens the path to monetising data infrastructure – an opportunity unavailable in the PSD2 era.

A. Direct monetisation (Data-as-a-Product)

FDSS schemes enable charging fees for sharing data. Whilst data required by regulation may be subject to regulated tariffs set by the scheme (to avoid monopolistic abuse), revenue potential lies in Premium APIs.

Premium API examples:

- Increased data refresh frequency: regulation may require sharing data with daily refresh. Premium API offers data with hourly, 15-minute or real-time refresh (real-time streaming). That’s valuable for trading platforms needing the freshest information about a customer’s available liquidity to enable them to immediately exploit market opportunities.

- Access to historical data exceeding regulatory requirements: regulation may require history for the last 12 months. Premium API offers 10 years of history for all investments, transactions and operations. Risk analysis algorithms or scoring models need long history to detect patterns in a customer’s financial behaviour.

- Enriched data: instead of raw transactions – account numbers, amounts and dates – the customer receives already pre-processed data. For example: transactions automatically categorised by expenditure types (food, transport, entertainment), calculated creditworthiness indicator based on flow analysis, and forecast of future expenditure based on historical patterns. BNP Paribas Securities Services identifies this as added value that business clients are willing to pay for.

Independent analyses conducted by Deloitte and McKinsey indicate that the total value of the Open Finance market in the European Union could reach €48bn by 2030 – nearly 50 billion euros of economic value generated by freer flow of financial data between institutions. The value comprises value-added services, Premium API fees and financial products enabled by access to a broader spectrum of data. Projections by Allied Market Research indicate part will fall precisely on interface monetisation.

B. Embedded Finance

FiDA is a driving factor in the Embedded Finance market’s development – a model where financial services are seamlessly embedded into non-financial platforms. As noted by Chris Skinner, the value of this market should reach $7.2 trillion by 2030.

Scenario: a customer buys a laptop for €5,000 in an online shop. At checkout, the e-commerce platform – using the bank’s API – verifies the customer’s creditworthiness in real time and offers financing in instalments, without filling in forms or redirecting to an external banking site. The process happens in the background, transparently, in under a few seconds. The customer receives an offer – “buy now, pay in 10 instalments of €530, instant decision” – which can be accepted with one click.

The strategy for banks involves becoming financial infrastructure providers (Banking-as-a-Service) for other industries – e-commerce platforms, telecommunications operators, ERP system developers for small and medium enterprises, and equipment manufacturers. Banks no longer compete for customers on their own websites – they provide the “financial mechanism” for partners who have contact with end customers. Revenue comes from commissions on granted loans, subscription fees for API access or revenue-share models with partners.

C. Cross-selling and up-selling based on competitor data

Operating as a FISP (Financial Information Service Provider), a bank can – with customer consent – aggregate data about all financial products the customer holds at other institutions. New opportunities open up.

Win-back strategy (recovering customers):

A bank aggregates customer data and discovers they have a mortgage at another bank with 6.5% annual interest. Current market rates are 5.2%, and this customer – after analysing the complete financial profile – qualifies for an even better rate, say 4.9%. The system automatically generates a refinancing offer: “Switch to us, reduce your monthly payment by €800, save €96,000 over the remaining loan period. The switching process takes 2 weeks, we’ll handle everything for you”. The customer sees measurable benefit. The bank recovers the customer.

Holistic wealth advice:

Having a picture of a customer’s wealth – accounts at three banks, share portfolio at a brokerage house, cryptocurrency on the Coinbase exchange and investment property financed by a loan at another bank – a financial advisor (or AI algorithm) can propose an optimised investment portfolio. For example: “We notice too much property sector exposure (50% of wealth), whilst for your risk profile the optimal level is 30%. We suggest reducing property allocation and increasing allocation in high-quality corporate bonds and globally diversified equity funds”. Deloitte Luxembourg suggests that recommendation based on data has far greater value than advice based only on products held at one bank.

A new business model emerges where value doesn’t come from “owning the customer” (lock-in) but from delivering the best services based on the broadest data access.

Evolution of the value chain: towards data-sharing ecosystems (FDSS)

The FiDA regulation forces decomposition of the traditional banking model, based until now on a vertically integrated value chain. In the new ecosystem, the centre of gravity shifts towards Financial Data Sharing Schemes (FDSS). These shouldn’t be perceived merely as technical transmission protocols. They’re data economy governance associations, forming the legal and operational foundation of the sector. The regulation introduces a requirement: both entities holding information (data holders) and those wanting to use it (data users) must belong to a scheme. Without this membership, operating in the market will be impossible.

Corporate governance within FDSS

FDSS structures’ tasks extend beyond system engineering. These organisations define rules across four planes affecting open finance profitability:

- Technology standards: schemes establish uniform data formats and API interfaces. The aim is eliminating barriers between IT systems that paralysed integration.

- Civil liability: determining liability rules is necessary. FDSS specifies who bears financial responsibility for data leakage or transmission error that distorts a customer’s credit history.

- Compensation models: FDSS define market mechanisms determining costs of building and maintaining infrastructure. This creates a settlement system where data sharing is a paid service.

- Arbitration: dispute resolution procedures are implemented, ensuring transaction stability and limiting court proceedings between market participants. Experts at KPMG International highlight that dispute resolution is a critical component.

In the banking environment, concern exists regarding corporate governance. The risk is that the biggest players – possessing capital and data volume – will impose prohibitive terms on smaller fintechs or cooperative banks. FiDA provisions require ensuring representativeness in governance bodies, protecting the interests of all stakeholder groups.

Existing initiatives set the direction of change:

- SPAA (SEPA Payment Account Access): a project developed by the European Payments Council (EPC), this is a reference model for FiDA implementations. As the European Payments Council describes, SPAA introduced pricing for “premium” services. This allows testing market readiness for a paid model for API infrastructure access.

- Berlin Group: a standardisation group, important in operationalising the PSD2 directive, is redefining its role. The Scheme² initiative notes that as the OpenFinance Taskforce, it designs technical standards for open finance and interoperability frameworks, which may accelerate implementations.

Power shift in the value chain: commoditisation risk

The new market architecture carries commoditisation risk. Financial institutions limiting themselves to the data holder role will become merely commodity suppliers (utilities). In this scenario, banks provide infrastructure whilst margins go to entities building the interface and customer relationship.

Organisations that integrate data from multiple sources will gain, creating financial “super-apps” – control centres for customers’ lives. Banks must prepare for rivalry with technology giants (Big Tech). The rivalry will play out in the User Experience area, where technology companies set the standards.

FiDA’s intersection with GDPR and eIDAS 2.0: compliance triangle

FiDA implementation occurs in the regulatory environment of GDPR and eIDAS 2.0. This interaction creates a “compliance triangle”, which represents an operational challenge but offers market advantage opportunity to those who master this complexity.

FiDA and GDPR: consent management

The regulations’ point of contact is permission dashboards. “Permission” in FiDA must be consistent with GDPR consent requirements.

The challenge is designing user interfaces. Making consent withdrawal too easy may deprive banks of access to historical data. KPMG International warns that cutting off information during a loan agreement will disrupt scoring models and risk assessment, destabilising the loan portfolio. The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) warns against excessive profiling. Legal analysis by Loyens & Loeff confirms systems must enforce the data minimisation principle – algorithms retrieve only information necessary for providing a specific service.

FiDA and eIDAS 2.0: identity transformation (EUDI Wallet)

The eIDAS 2.0 regulation introduces the European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI Wallet), which will become the backbone of the FiDA ecosystem.

Insights from McDermott Will & Emery suggest this solution will eliminate PSD2 era problems: cumbersome login and redirects that increased abandonment rates. The EUDI Wallet will set the standard for strong authentication (SCA) and enable attribute sharing, such as age or tax residency. Combining financial history from FiDA with verified identity from eIDAS 2.0 will allow remote onboarding of cross-border customers. The European Commission outlines how banking groups will gain the ability to centralise Know Your Customer (KYC) processes, translating into operational savings.

New competitive dynamics: Big Tech, crypto and access gatekeepers

FiDA changes the competitive roadmap. The regulation opens the market to players from outside the financial sector and limits technology giants’ dominance.

Big Tech asymmetry and gatekeepers

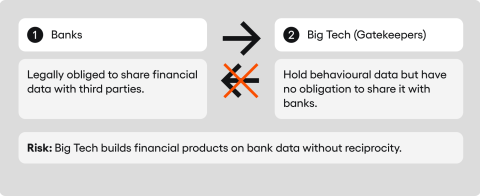

The status of gatekeepers from the Digital Markets Act (DMA), such as Apple, Google, Amazon or Meta, remains a negotiation topic.

The banking sector points to power asymmetry. Commentary on the Oxford Business Law Blog points to power asymmetry, noting Big Tech possesses data about consumer behaviours that they don’t share on reciprocal terms. Simultaneously, through a FISP licence they would gain insight into financial data accumulated by banks.

The European Parliament and Council are processing amendments to exclude gatekeepers from obtaining FISP status. Documents from the CCIA discuss this mechanism, supported by European banking lobby (EBF), which aims to prevent market monopolisation and using data for ad targeting. Financial institutions must consider the scenario where full exclusion doesn’t come into force, though. Then they face rivalry in the interface layer, where Big Tech holds design advantage.

Crypto market integration (MiCA)

The legislator has included crypto-asset service providers (CASPs) in the data holder definition.

This creates new reality in wealth management. Banks will gain the ability to automatically retrieve data about customers’ balances on cryptocurrency exchanges (e.g. Binance, Coinbase). KPMG International envisions including this information in private banking (Wealth Management) systems will allow risk assessment and advice based on the customer’s actual portfolio. The threat is that crypto exchanges with a FISP licence may start offering services based on traditional assets, becoming competition for retail banks.

Strategic use case scenarios in the B2B segment

Financial services evolution has shown that Open Banking, initiated by the PSD2 directive, focused primarily on the retail market, offering tools for account aggregation or personal finance management. From a macroeconomic perspective, however, it’s the FiDA regulation (Financial Data Access) that opens the path to building business value. The greatest growth potential and main driving force of modern finance lies today in the B2B segment, encompassing the SME sector and corporate clients.

SME sector financing: from uncertainty to algorithmic precision

Small and medium enterprises have struggled for decades with the so-called financing gap, estimated globally at trillions of dollars. Where does this problem originate? Primarily from information asymmetry and lack of reliable, current data that would allow banks to properly assess smaller entities’ credit risk. In the traditional model, this process is manual and burdensome, making it simply unprofitable for institutions with small financing amounts.

FiDA’s legal framework introduction significantly changes this dynamic. A financial service provider, operating as a bank or specialised fintech, gains the ability to automatically and securely retrieve data from multiple sources simultaneously.

In practice, this means the system no longer needs to rely on historical declarations but on data retrieved in real time. It can analyse:

- Current cash flows directly from customer bank accounts.

- Accounting and ERP systems, providing insight into issued and paid invoices.

- E-commerce platforms, delivering precise information about sales volume and purchasing trends.

- Insurance and leasing registers, building a complete picture of company obligations.

Consequently, institutions can implement modern financing models based on actual flows. Credit decisions stop being processes stretched over weeks, becoming swift algorithmic operations instead. Examples from developed markets, such as the Lendio platform in the USA or pilot projects in the European Union, clearly indicate that decision-making time shortens from several weeks to merely several minutes. The Euro Banking Association reports that decision-making time shortens significantly.

ESG and sustainable development reporting automation

Data concerning environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) factors have ceased performing merely an image function. They’ve become a hard reporting requirement resulting from the CSRD directive and EU Taxonomy. For most companies, obtaining them currently poses considerable operational challenge, requiring manual searching through invoices, certificates and declarations.

Thanks to FiDA regulations, this process may undergo far-reaching automation. Banks and insurers, acting as data holders, will be able to share standardised information about “green” attributes of financed assets.

Imagine a specific scenario: a bank verifies the energy class of property serving as loan security or precisely assesses a vehicle fleet’s emissions under leasing, without needing to engage the client in time-consuming documentation gathering.

Such an approach opens the door wide to offering so-called green loans. Banks gain the ability to propose preferential financing terms to SME sector companies that prove through FiDA systems they possess environmental certificates or investments in sustainable funds. Trends identified by Capgemini show the entire process happens digitally, eliminating paper documentation circulation and significantly reducing error risk.

Legislative timeline: time for strategic decisions

The legislative process around FiDA is already very advanced. Whilst final implementation deadlines remain subject to negotiation, they establish a clear time horizon that must be considered in corporate strategies for the coming years.

Table 2: FiDA regulation implementation roadmap

| Phase | State of knowledge as of January 2026 | Key milestones and strategic actions |

| Finalisation of negotiations (trilogues) | Q1 – Q2 2026 | This is the current legislative status. Trilateral negotiations are ongoing between the Commission, Council and Parliament following the Council’s mandate in December 2024. Negotiations primarily concern the role of technology giants (gatekeepers) and reassessment of implementation costs. |

| Legal adoption and publication | Q3 / Q4 2026 | Official adoption of the regulation and its publication in the Official Journal of the EU is expected. Provisions will come into force 20 days after publication, which will only then formally start the implementation clock for financial institutions. |

| Market formation phase | 2027 – mid-2028 | This will be a critical transitional period (typically 18–24 months) for establishing data-sharing schemes. During this time, the European Banking Authority will issue detailed technical standards, and banks and insurers will need to adapt their IT systems. |

| Application date for provisions | mid-2028 / 2029 | Moment of full entry into force of obligations. Data holders will need to share data on demand, and customers will gain access to consent management dashboards. The first real products based on new provisions will appear on the market. |

| Full market maturity | 2030+ | The ecosystem will stabilise and the regulation may extend to products initially excluded. Full integration of financial services with the European digital identity wallet is also expected then. |

The most important strategic conclusion flows from analysis of years 2027–2028. This is a time that can be termed “competition for standards”. Institutions that overlook this moment and don’t actively engage in creating data-sharing schemes will find themselves in a difficult situation. Documents from the Council of the European Union suggest they will be forced to adapt solutions imposed by market leaders or the regulator, which may permanently weaken their competitive position.

Conclusions and key board recommendations

FiDA regulation is an inevitable process that will define European financial sector architecture for the coming decade. We face a significant business model shift: banking evolves from the traditional “money vault” role towards a modern “data vault”.

Key strategic recommendations

- Transformation into a data-driven organisation: boards must start treating customer databases as high-value balance sheet assets. Future strategy must assume active monetisation of these resources through paid Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and building new products based on external data aggregation.

- Active participation in scheme creation: creating market standards is too important a matter to leave exclusively to IT departments. Boards must delegate business representatives to national and EU working groups. Only this way can institutions genuinely shape fee models and governance rules within schemes, defending institutional interests against global technology giants’ dominance.

- Investment in real-time architecture: core system modernisation, particularly in the insurance and investment sectors, becomes a pressing necessity. These expenditures shouldn’t be treated as FiDA regulatory costs but as essential digitalisation investment, of which the regulation is merely a powerful catalyst.

- Ecosystem strategy: independent building of all innovative solutions is now impossible and economically inefficient. Technology partners should be identified, such as agile fintechs, for collaboration in embedded finance models. This allows exploiting their speed whilst maintaining full control over customer relationships and regulatory compliance.

- B2B as priority growth area: whilst the retail market is already heavily saturated, the SME segment and corporate clients (e.g. in credit automation or ESG reporting areas) currently offer the greatest return on investment potential in open finance.

FiDA is essentially a digital competence test for European financial leaders. Those who treat it merely as another regulatory compliance exercise risk marginalisation. Meanwhile, those who exploit these changes for deep operational model reconstruction will gain access to a new data economy worth hundreds of billions of euros.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the Financial Data Access FiDA regulation proposed by the European Union?

The Financial Data Access FiDA regulation is a transformative framework creating a single market for financial data across the European Union. By extending the model beyond payments to nearly all financial products, it forces the financial services sector to shift from regulatory defense to aggressive API monetization. The sector estimates implementation could cost up to €36 billion.

Which data categories fall under the scope of Access FiDA?

The Financial Data Access scope covers a broad range of assets managed by the financial industry. Key categories include:

- Mortgage credit agreements, consumer loans, and credit lines (including repayment history).

- Savings and insurance based investment products like unit-linked funds, effectively functionally similar to other investment categories.

- Occupational retirement provision schemes (PPE, PPK) and non life insurance products (excluding health).

- Crypto-assets, aligning with the MiCA regulation.

Who are the data owners and regulated entities in this ecosystem?

Conceptually, customers act as data owners who must grant consent via permission dashboards. The ecosystem involves:

- Data Holder: The entity where customer data held resides (e.g., banks).

- Financial Information Service Provider (FISP): An entity authorized by a competent authority to access data.

- Data User: Any entity acting essentially as a data controller regarding purpose limitation, strictly adhering to General Data Protection Regulation rules to avoid penalties.

How do Data Sharing Schemes manage financial data access?

Mandatory data sharing schemes (FDSS) govern the ecosystem, defining liability and data quality standards. Unlike previous free models, these schemes allow charging fees for required technical interfaces. This governance structure aims to resolve disputes internally, potentially reducing the reliance on a legal representative for external court litigation between participants.

How does the regulation impact the Financial Services Industry?

FiDA triggers a digital transformation, enabling data driven financial services. By allowing the free movement of data between ERP, banking, and e-commerce systems, the financial services industry can automate credit scoring. This creates significant economic benefits, reducing analysis time from weeks to minutes and closing the SME financing gap.

What are the security requirements for Access FiDA?

To facilitate access FiDA, providers must implement high-availability APIs and robust security measures. While the source text focuses on cyber risk management found in frameworks like the Digital Operational Resilience Act, it specifically mandates that FISPs meet strict authorization requirements regarding operational security and governance to protect data access rights.

How does Financial Data Access differ from the Payment Services Regulation?

Financial Data Access evolves beyond the Payment Services Regulation (PSD2) by introducing a paid market model. While the Revised Payment Services Directive focused on free access to payment accounts, FiDA allows monetizing access financial data. This incentivizes “Premium APIs” offering enriched data for personalised services and holistic advice.

What is the timeline involving Council positions and implementation?

The legislative process is advanced, with Council positions and the European Parliament negotiating final terms. The “competition for standards” phase (2027–2028) is critical. Institutions must engage with the Council of the European Union working groups now to shape the schemes before financial data access regulation obligations fully apply around 2029.

How does the framework address data protection and suitability assessments?

The regulation mandates that suitability and appropriateness assessments can be automated using real-time data. However, strictly sensitive data is excluded to ensure data protection. Supervision by European Supervisory Authorities (like the EBA or EIOPA) ensures that data driven innovation respects privacy while enabling the proposed framework of Open Finance.

This blog post was created by our team of experts specialising in AI Governance, Web Development, Mobile Development, Technical Consultancy, and Digital Product Design. Our goal is to provide educational value and insights without marketing intent.